Epis and monos

This post is on pages 29 through 33 of Awodey. It took me a while to do this, because I was basically on holiday for the past week.

The definition of a mono and an epi seems at first glance to be basically the same thing as “injection” and “surjection”. A mono is \(f: A \to B\) such that for all \(g, h: C \to A\), if \(fg = fh\) then \(g=h\). Indeed, if we take this in the category of sets, and let \(g, h: {1 } \to A\) (“picking out an element”), we precisely have the definition of “injection”. An epi is \(f: A \to B\) such that for all \(i, j:B \to D\), if \(if = jf\) then \(i=j\). Again, in the category of sets, let \(i, j: B \to {1}\); then… ah. \(if = jf\) and \(i=j\) always, because there’s only one function to the one-point set from a given set. I may have to rethink the “surjection” bit.

Then there’s Proposition 2.2, which I’m happy I’ve just basically proved anyway, so I skim it.

Example 2.3: “monos are often injective homomorphisms”. I glance through the example as preparation for going through it with pencil and paper, and see “this follows from the presence of objects like the free monoid \(M(1)\)”, which is extremely interesting. Now I’ll go back through the example properly.

Suppose \(h: M \to N\) is monic. For any two distinct ways of selecting an element of the monoid’s underlying set, we can lift those selections into mappings on the free monoid \(M(1) \to M\); they are distinct by the UMP. Applying \(h\) then takes the mappings into \(N\), maintaining distinctness by monicity; then the UMP lets us drag the mappings back into the sets, making selections from \(1 \to \vert N \vert\). The converse is quite clear.

So it is clear where we needed the free monoid and its UMP: it was to give us a way to pass from talking about monoids to talking about sets, and back.

Example 2.4: every arrow in a poset category is both monic and epic. An arrow \(f: A \to B\) is monic iff for all \(g, h: C \to A\), \(f g = f h \Rightarrow g = h\). That is, to abuse notation horribly, \(a \leq b\) is monic iff \(c \leq a \leq b, c \leq a \leq b \Rightarrow ((c \leq a) = (c \leq a))\). Ah, it’s clear why all arrows are monic: it’s because there is at most one arrow between \(A, B\), so two arrows with the same codomain and domain must be the same. The same reasoning works for “the arrows are epic”.

“Dually to the foregoing, the epis in the category of sets are the surjective functions”. This is the bit from earlier I had to rethink. OK, let’s take \(f: A \to B\) an epi in the category of sets. Let \(i, j: B \to C\), for some set \(C\). (Hopefully it’ll become clear what \(C\) is to be.) Then \(i f = j f\) implies \(i = j\); we want to show that \(f\) hits every element of \(B\), so suppose it didn’t hit \(b\). Then when we take the compositions \(if, jf\), we see that \(i, j\) never are asked about \(b \in B\), so in fact we are free to choose \(i, j\) to differ. That means we just need to pick \(C\) to be a set with more than one element. OK, that’s much easier, although it’s not quite clear to me how this is “dually”.

Then the example of the inclusion map \(i\) of the monoid \(\mathbb{N} \cup { 0 }\) into the monoid \(\mathbb{Z}\). We’re going to prove it’s epic, so I’ll try that before reading the proof. Let \(g, h: \mathbb{Z} \to M\) for some monoid \(M\); we want to show that \(g i = h i \Rightarrow g = h\). Indeed, suppose \(g i = h i\), but \(g \not = h\): that is, there is some \(z \in \mathbb{Z}\) such that \(g(z) \not = h(z)\). Since \(gi = hi\), we must have that \(i\) does not hit \(z\): that is, \(z < 0\). But \(gi(-z) = hi(-z)\) and so \(g(-z) = h(-z)\); whence \(g(0) = g(z)+g(-z) \not = h(z)+h(-z) = h(0)\). That is, \(g, h\) differ in the image of the unit. That is a contradiction because a homomorphism of monoids has a defined place to send the unit.

Looking back over the proof in the book, it’s basically the same. Awodey specialises to \(-1\) first.

Proposition 2.6: every iso is monic and epic. I can’t help but see the diagram when I read this, but I’ll try and ignore it so I can prove it myself. Recall that an iso is an arrow such that there is an “inverse arrow”. Let \(f: A \to B\) be an iso, and \(i, j: B \to C\) such that \(if = jf\). Then we may post-compose by \(f\)’s inverse - ah, it’s clear now that this will work both forwards and backwards. This is exactly analogous to saying “we may left- or right-cancel in a group”, and now I come to think of it, “epis are about right-cancelling” is something I just skipped over in the book.

I’m happy with “every mono-epi is iso in the category of sets”, since we’ve already proved that the injections are precisely the monos, and the epis are precisely the surjections.

Now, the definition of a split mono/epi. That seems fine - it’s a weaker form of mono/epi. “Functors preserve identities” does indeed mean that they preserve split epis and split monos, clearly, because a split epi comes in a pair with a split mono.

The forgetful functor Mon to Set does not preserve the epi \(\mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{Z}\): we want to show that the inclusion of \(\mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{Z}\) (as sets) is not surjective. Oh, that’s trivially obvious.

In Sets, every mono splits except the empty ones: yes, we already have a theorem that injections have left inverses. “Every epi splits” is the categorical axiom of choice: we already have a theorem that “surjections have right inverses” is equivalent to AC, so I’m happy with this bit.

Now the definition of a projective object. It’s basically saying “arrows from this object may be pulled back through epis”. A projective object “has a more free structure”? I don’t really understand what that’s saying, so I’ll just accept the words and move on.

All sets are projective because of the axiom of choice? Fix set \(P\); we want to show that for any function \(f: P \to X\) and any surjection \(e: E \to X\), there is \(\bar{f}: P \to E\) with \(e \circ \bar{f} = f\). We have (by Choice) that \(e\) splits: there is a right inverse \(e^{-1}\) such that \(e \circ e^{-1} = 1_X\). Define \(\bar{f} = e^{-1} \circ f\) and we’re done.

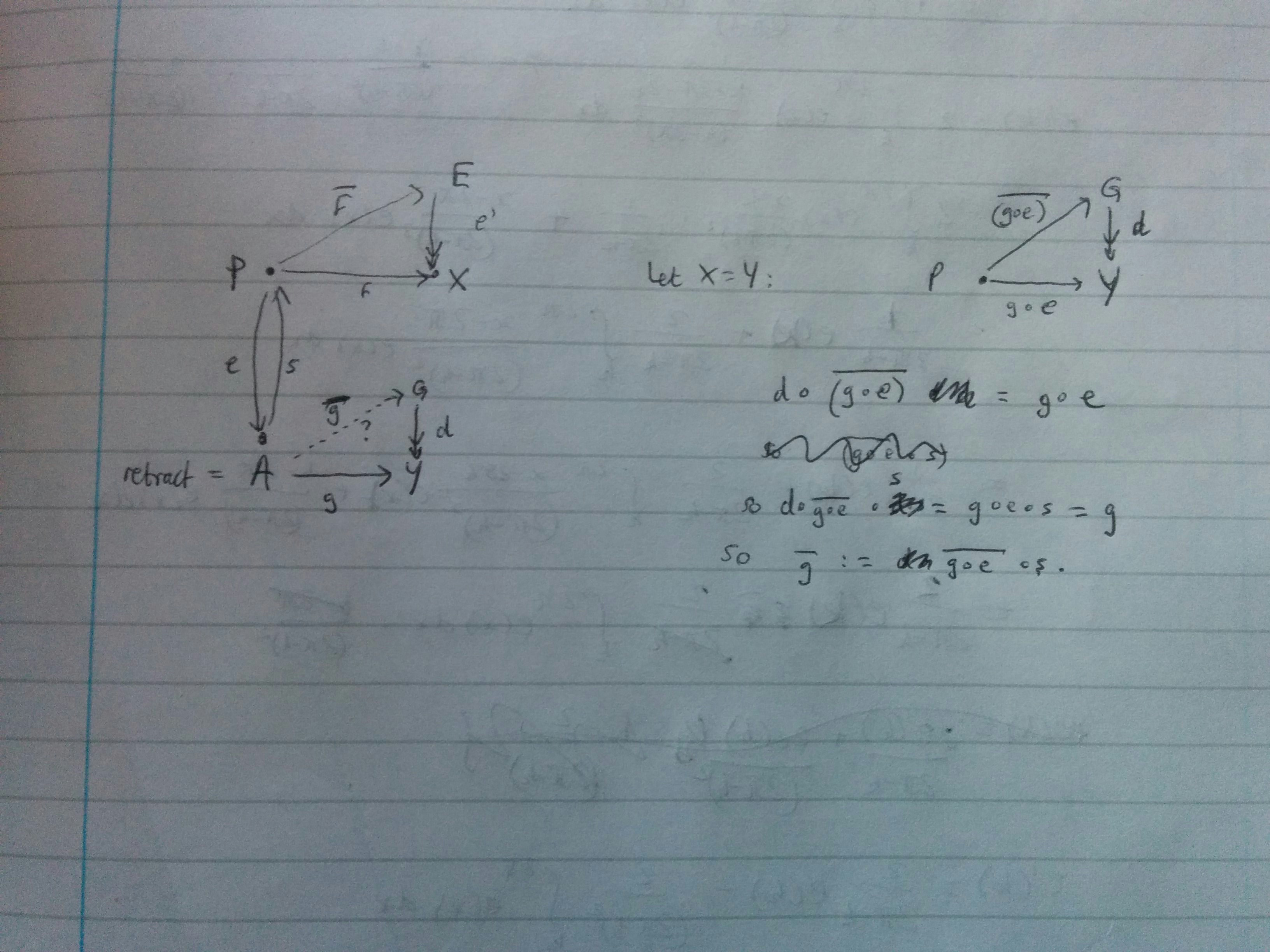

Any retract of a projective object is itself projective: I absolutely have to draw a diagram here. After a bit of confusion over left-composition happening as you go further to the right along the arrows, I spit out an answer.

Summary

This section was more definitional than idea-heavy, so I think I’ve got my head around it for now. I do still need to practise my fluency with converting compositions of arrows on the diagrams into composition of arrows as algebraically notated - I still have to keep careful track of domain and codomain to make sure I don’t get confused.