Products in category theory

This is on pages 38 through 48 of Awodey. I’ve been looking forward to it, because products are things which come up all over the place and I’d heard that they are one of the main examples of a categorical idea.

I skim over the definition of the product in the category of sets, and go straight to the general definition. It seems natural enough: the product is defined uniquely such that given any generalised element of the product, it projects in a unique way to corresponding elements of the children.

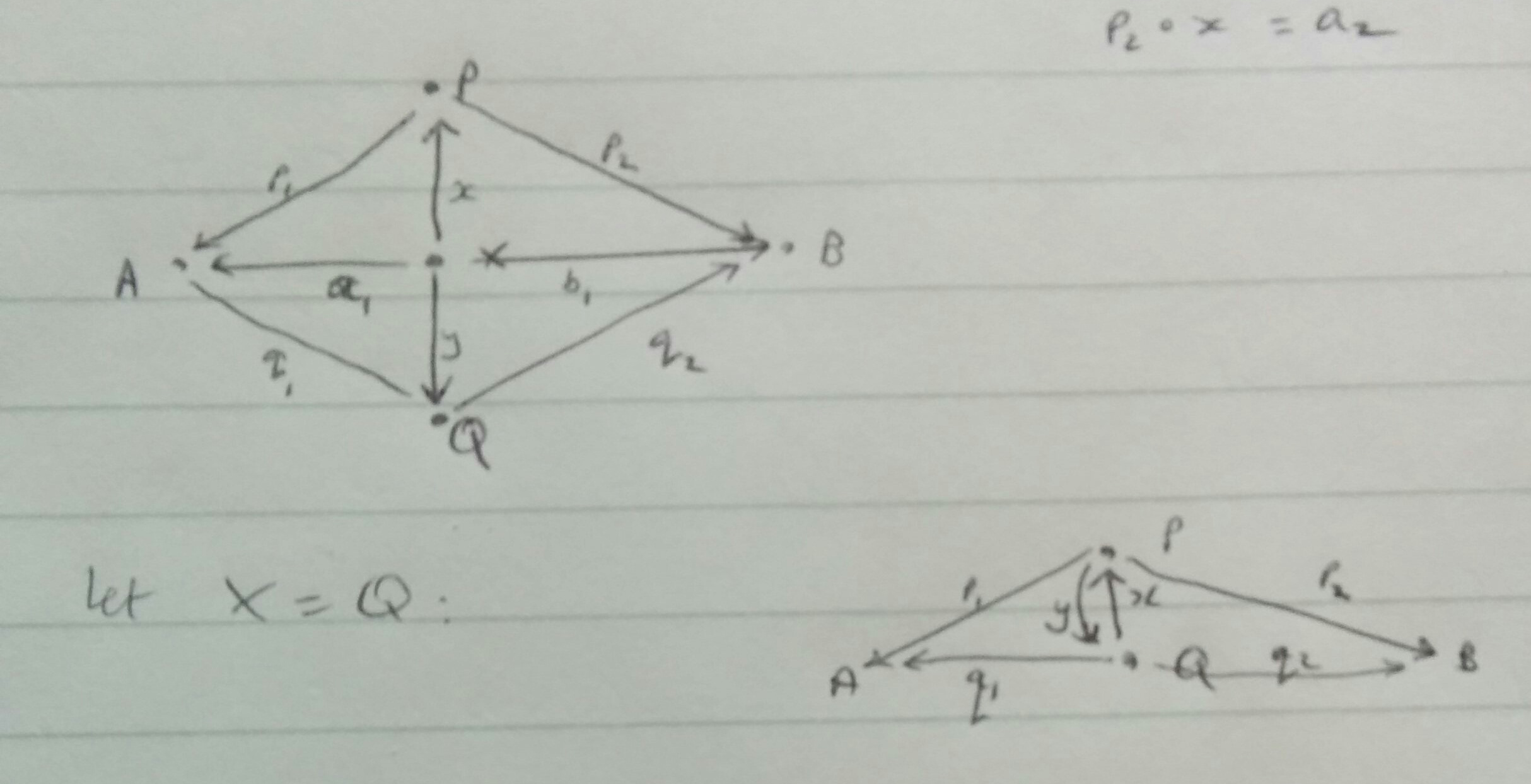

Proving that products are unique up to isomorphism presumably goes in the same way as the other UMP-proofs have gone. I draw out the general diagram, then because we need to show isomorphism of two objects, I replace the “free” (unspecified) test object with one of the two objects of interest. Then the uniqueness conditions make everything fall out correctly. Moral: if we have a mapping property along the lines of “we can find unique arrows to make this diagram commute” then everything is easy.

Then we introduce some notation for the product. “A pair of objects may have many different products in a category”. Yes, I can see why that’s plausible, because we could define \(\langle a, b \rangle\) to be the ordered pair \((b, a)\), for instance, without changing any of the properties we’re interested in.

“Something is gained by considering arrows out of products”: I’m aware of currying, which when Awodey points it out, makes me think nothing is really gained after all. I think I’ll wait for Chapter 6 before I pass judgement on that.

Now for a huge list of examples. First there are two definitions of “ordered pair”, which I called earlier (though not in this exact form). Then we see the usual products of structured sets, with which I’m already very familiar.

I’ll verify the UMP for the product of two categories: let \(x_1: X \to C, x_2: X \to D\) be generalised elements. We want there to be a unique arrow \(u : X \to (C \times D)\) with \(p_1 u = x_1, p_2 u = x_2\), where \(p_1, p_2\) are the projection functors. Certainly there is an arrow given by stitching \(x_1, x_2\) together componentwise; is there another? Clearly not. Suppose \(u_2\) were another arrow \(u: X \to (C \times D)\). If \(u_2(x) = (c, d)\) then \(p_1 u_2(x) = c\) by the UMP, and \(u_2\) is therefore specified on all generalised elements already. That argument is not very formal, and I don’t really see how to formalise it properly.

The product of two groups according to this product construction is then self-evidently the product group we know and love. The product of two posets is also manifestly a poset, being a category where any pair of objects has at most one arrow between them. (Indeed, if there were two, we could project down to one of the posets to obtain two arrows between two elements.)

The greatest lower bound example takes me a while to get my head around. The UMP for the product says, “define \(p \times q\) such that for all \(x\), if \(a \leq p \times q, b \leq p \times q\), and \(a \leq x, b \leq x\), then \(x \leq p \times q\)”. That is indeed the greatest lower bound, but it took me ages to work this out.

I work through the topological spaces example without thinking too hard about it. It’s not clear to me that Awodey has proved that the uniqueness part of the UMP is satisfied, but I’ll just accept it and move on.

Type theory example: I’ve already met the lambda calculus, though never studied it in any detail. I skim over this, pausing at the equation “\(\lambda x . c x = c\) if no \(x\) is in \(c\)” - is this a typo for \(\lambda x . c = c\)? No, stupid of me - \(c\) represents a function, and the function \(x \mapsto c(x)\) is the same as the function \(c\). Then the category of types is indeed a category, and I’m happy with the proof that it has products. This time Awodey does certainly verify the uniqueness part of the UMP, by simply expanding everything and reducing it again.

A long remark on the Curry-Howard correspondence. Clearly the product here is conjunction - skimming down I see that Awodey says it is indeed a product (or, at least, that there is a functor from types to proofs in which products have conjunctions as their images). Very pretty.

“Categories with products”: supposing every pair of objects has a product, we define a functor taking every pair to its product. That’s intuitive in the sense of “structured sets”, since I’m very familiar with that product construction. What does it mean in the poset case? Recall that the product was the greatest lower bound. A poset where every pair of elements has a greatest lower bound is actually a totally ordered set, and the greatest lower bound is the least of the two elements, so that also makes sense. I think I’ll skip over the UMPs for \(n\)-ary products, but the idea of a terminal object as a nullary product is pretty neat. So that’s why the empty product of real numbers is 1.

Summary

As seems to be a general theme, I understand the syntax of products, and I can recognise some of them when they turn up, but have no real intuition for how they work. There will be more examples at the end of the chapter, which should clear things up a bit.