Limits and pullbacks

I’m going to skip pages 85 through 88 of Awodey for the moment, because time is starting to get short and I want to make sure I’m doing stuff which is relevant to the Part III course on category theory. Therefore, I’ll skip straight to Chapter 5, pages 89 through 95. (There’s not really a nice way to break this chapter up into small chunks, because the next many pages are on pullbacks.)

We have indeed seen that every subset of a set is an equaliser: just define two functions which agree on that subset and nowhere else. (The indicator function on the subset, and the constant-1 function, for example.) A mono is a generalised subset: well, we have that arrows are generalised elements, so can we make a mono represent a collection of generalised elements? Yes, sort of: given any generalised element which is “in the subset” - that is, on which the equaliser-functions agree - that element lifts over the mono, so can be interpreted as an element of the mono. It’s a bit dubious, but it’ll do.

The idea of “an injective function which is isomorphic onto its image” comes up quite often, so the next chunk is quite familiar. Then the collection of subobjects of \(X\) is just the slice \(\mathbf{C}/X\), and the morphisms are the same as in the slice category: commuting triangles.

Because our arrows are monic, we can have at most one way to complete any given commuting triangle, so we get the natural idea of “there is exactly one natural inclusion map from a subset to its parent set”. Finally, we define what it means for two objects to be “the same object” in this setting: namely, each includes into the other. (Remark 5.2 describes the process of quotienting out those objects which are “the same” in this sense, and points out that in Set, each subobject is isomorphic only to itself.)

We then see that subobjects of subobjects of \(X\) are subobjects of \(X\), because the composition of monic things is monic. We therefore have a way of including subobjects of subobjects of \(X\) into \(X\), and that lets us define the obvious membership relation.

The final example in this section is that of the equaliser, which is actually a subobject consisting of generalised elements which \(f, g\) view as being the same. I follow this construction as symbols, but as ever, I don’t really have an intuition for it. I’ll accept that and move on.

Pullbacks next. A pullback is a universal way of completing a square. My first thought on seeing the definition is that this is an awful lot like a product: given \(f: A \to C, g: B \to C\) we seek a product of \(A\) and \(B\) such that the projection diagram commutes with \(f\) and \(g\) in the right way. However, products are unique up to isomorphism, so there is “only one” product anyway: we can’t just look for one which behaves in the right way, can we?

I’m going to have to try and get this in Sets. Let \(A = { 1, 2 }\), \(B = {4, 5 }\), \(C = {1, 2, 4, 5 }\) and \(f, g\) the inclusions. Then the pullback \(P\) must be the empty set - ah, this is the intersection operation Awodey mentioned earlier, and I sense an equaliser going on here. What about \(A = {1, 2, 4 }\) instead? Then we need \(P\) to be \({4}\) only.

Ah, I understand my confusion. Products are indeed unique - but they are universal: they are the most general kind of thing which satisfies the UMP of the product. There are other things which satisfy the “UMP-without-the-U” of the product: the statement of the UMP but without the word “unique”. We want to pick the most general one of those which satisfies a certain property. So a product is just a pullback where \(C\) is initial, for instance.

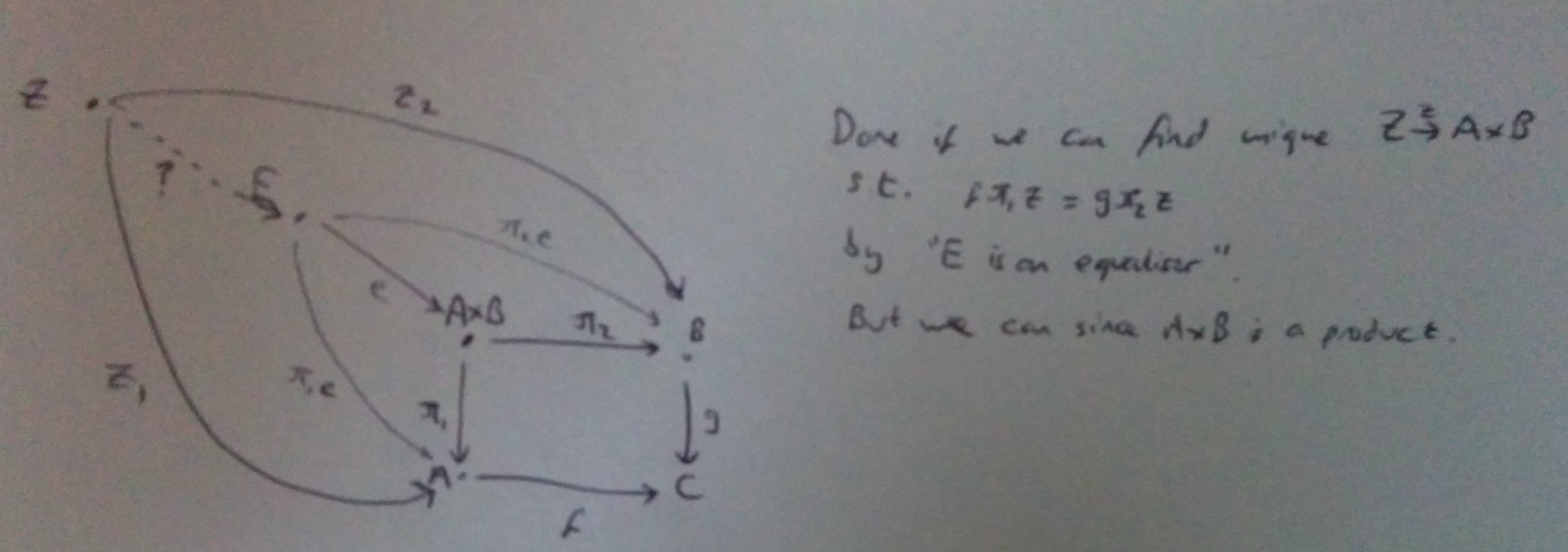

Proposition 5.5 is a description of the pullback as an equaliser. I knew there would be something like this! Without looking at the proof, I can tell it’ll revolve around the fact that equalisers are monic (that’ll be the step which guarantees uniqueness). The proof follows just by drawing out the diagram, really.

Now comes a demonstration that inverse images are a kind of pullback. I don’t see a way to understand this intuitively enough that I could reproduce it - the idea is simple but very much counter to my intuitions. I’ll just plough on.

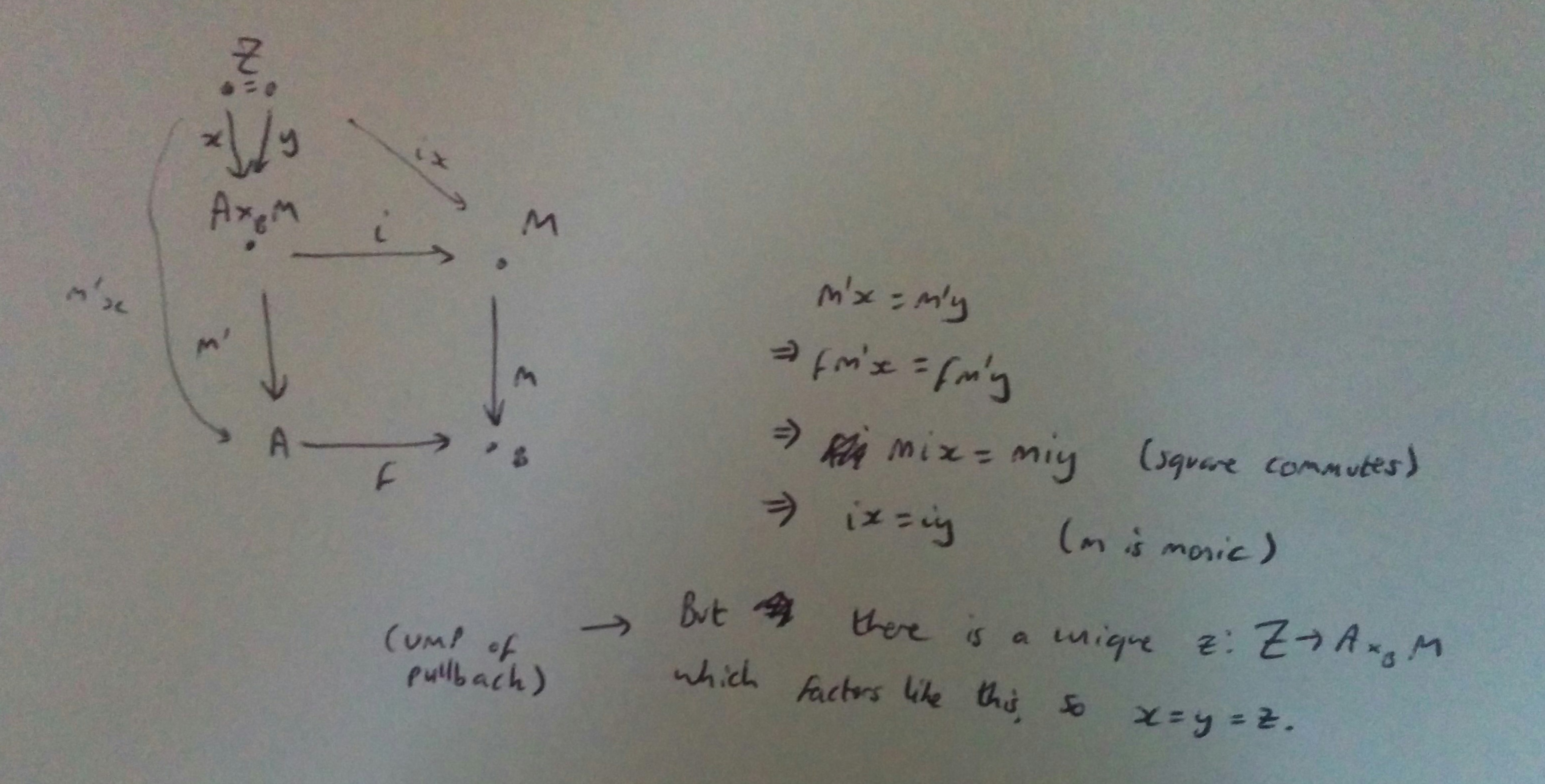

In a pullback of \(f: A \to B, m: M \to B\), if \(m\) is monic then its parallel arrow \(m’\) is: that follows from another diagram.

Summary

I get the impression that the idea of a limit is a very general one, of which presumably pullbacks are a specific example - I can’t think of something which generalises the idea of “inverse image” off the top of my head. We’re going to have six more pages on pullbacks, and then the idea of a limit will be introduced. (This chapter is rather long.)

I do like the way Awodey is doing this: give examples of specific constructions, and then show how they may be unified. I glanced down to the blurb at the start of the “limits” section, and saw that another such unification is about to take place. I’m looking forwards to that.